Design That Grounds a Legacy

Landscape Design Services

Bespoke Outdoor Environments for the Brandywine Valley

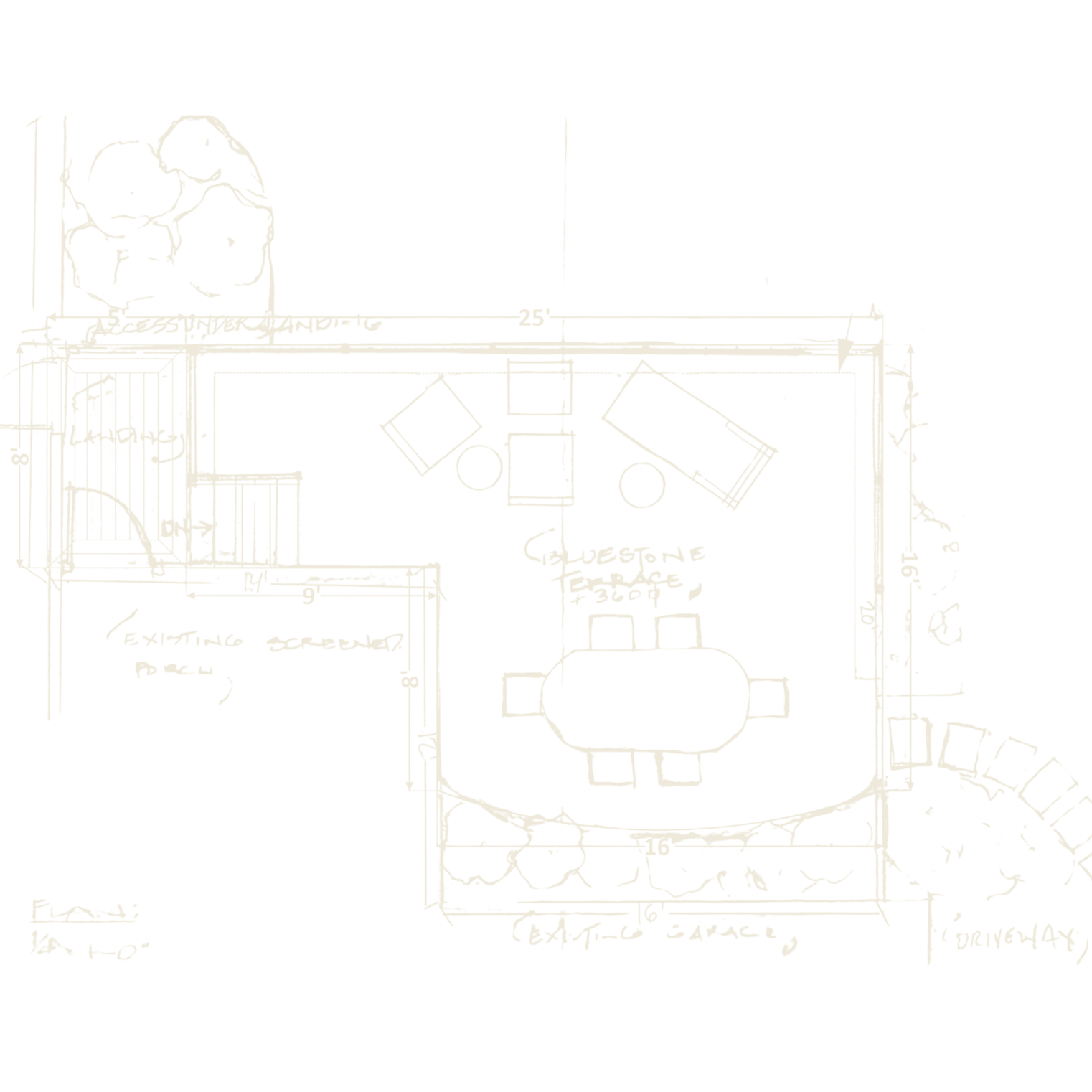

Our design process starts with deep site understanding and ends with one-off environments built to endure, no kits, no square-foot pricing, just smart layouts and honest materials. We offer both detailed 2D plans for permitting and layout, and immersive 3D renderings to help you visualize spaces like kitchens, terraces, and transitions, so everything’s clear before the first shovel hits the ground.

What We Design Says Everything About How We Build

Good design isn’t decorative. It’s decisive. At Brandywine, we approach landscape design like a master builder approaches a foundation—with permanence in mind from the first line drawn.

We start with the site—its slope, flow, sun, soil, and context. Then we shape a layout that solves problems before they happen: grading, drainage, access, and use. Whether it’s a hillside pavilion or a tight courtyard, every plan is a one-off—hand-built on screen or paper, designed to make sense not just today, but 20 years from now.

We’re not here to draw something “pretty.” We’re here to create something you can build once, live with forever, and pass down. This isn’t landscaping. It’s design that anchors legacy.

How it Works

01

Start the Conversation

Submit a quick form or give us a call. We schedule your site consultation and align on high-level goals.

02

Design Proposal & Budget

We issue a paid design proposal based on a rough budget (3% of project value). That fee is credited back if you move forward.

03

Design Development

Hand renderings, 2D plans, and 3D visuals ensure you understand every detail before construction begins.

04

Fixed-Cost Agreement

No surprises. No change orders. Just a locked-in number and a plan to execute it.

05

Build, Start to Finish

When we start your project, we stay on it until it’s done. Same crew, same standard, from prep to final capstone.

“From day one, Brandywine provided fair, accurate pricing—no surprises, ever. Every cost-related change was discussed in advance, and we always felt like we were in good hands. The crew was punctual, professional, and worked hard every single day. If you're looking for a team to build the backyard you've been waiting for, look no further.”

— Adam R., via Facebook

When Clients Talk, Craftsmanship Speaks.

•

When Clients Talk, Craftsmanship Speaks. •

Serving the Main Line & Brandywine Valley Region

We create enduring outdoor landscape environments and custom backyard designs that reflect your identity and our craft.